Those with only a passing interest in gay culture will no doubt have heard of drag queens, aided by the meteoric rise of US reality TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race, which recently finished its ninth season. But perhaps fewer have heard of their corollary, drag kings.

Those with only a passing interest in gay culture will no doubt have heard of drag queens, aided by the meteoric rise of US reality TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race, which recently finished its ninth season. But perhaps fewer have heard of their corollary, drag kings.

A ‘drag queen’ refers to a man, usually gay, dressed as a woman for the purposes of entertainment. Likewise a ‘drag king’ can be loosely described as an individual (usually a woman, but also people who identify as other genders) who consciously performs masculinity.

Drag kings became a significant part of lesbian and queer women’s lives globally from the late 1980s. Events featuring drag king performances were an important part of queer culture: the performances often were seen as ways to explore gender and sexuality, and they commonly took place in gay- and lesbian-friendly venues. This meant that drag king events were often associated with ‘safe spaces’ and formed the basis of thriving social scenes.

In recent years drag king performances globally have declined in popularity and were in danger of fading from our cultural view. The reasons behind this are many, including the fact that the debate around gender is evolving, and drag is seen by some as increasingly problematic. But recently, there’s been a resurgence of more inclusive forms of drag culture in Australia, and new kings are taking the stage.

Games of thrones

While both performance styles come under the umbrella term of ‘drag’, kings and queens have different origins and have evolved in different ways. The word ‘drag’ most like comes from 19th century theatrical cross-dressing, and is now commonly associated with gay or camp comedy.

Traditionally, drag queens are seen as parodying the characteristics associated with women. We immediately think of drag queens with big hair and overdone make-up, and body language that conforms to stereotypical ‘female’ behaviour (though not all drag queens do perform this type of exaggerated femininity). This in effect draws attention to what the 18th century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau referred to as the ‘artifice of femininity’, or the excessive ornamentation and self-display of women.

Performing masculinity, as drag kings do, is arguably more difficult. Masculinity is perceived as more natural or ingrained than femininity, so drag kings can’t simply dress up but have to rely on other performance techniques.

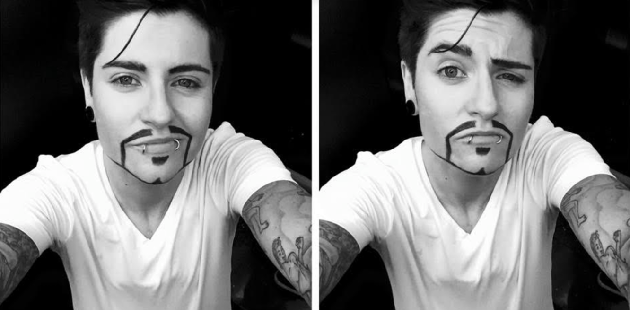

Some drag kings ‘strap and pack’ (binding their breasts to give the appearance of a flat chest and wearing a dildo or other similarly shaped object to give the impression of male genitalia). Others draw on or glue hair to indicate facial growth, manly eyebrows or chest hair.

Some drag kings are known for their sexy, smooth dancing style, some for their realistic impressions of masculine walk, posture and gesture, and yet others for their comic renditions. Some drag kings provide for more politically-motivated critique in their performance, while others just want to get up on stage and have a good time.

Just as drag queens are associated with gay culture, drag kings are associated with lesbians, but not all performers are gay or lesbian. Likewise, king performers see themselves as distinct from other male impersonators, such as British music hall star, Vesta Tilley, lesbians who dress or act in ‘butch’ manner, and other reasons women might try to pass as men. Though, in practice these distinctions are more difficult to make.

Drag queens have achieved as a ubiquitous presence at pride festivals and as a form of entertainment in theatre, music and movie industries for both gay and straight audiences – consider the ongoing appeal of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. Drag kings haven’t yet made it into the mainstream, and remain somewhat of a subcultural phenomenon.

Golden age

Globally, drag king culture took root almost simultaneously from the 1990s onwards in lesbian nights, bars and clubs in major cities. Many attribute the origins of a distinctive drag king scene in Australia to performer D-Vinyl’s earlier ground-breaking shows from 1999 and the drag king competition, DKSY held between 1999 and 2000 where experimental drag artists, The Kingpins, performed.

In 2002, drag king legend Sexy Galexy created a weekly event called Kingki Kingdom (renamed Queer Central in 2005) that quickly became an institution within Sydney’s lesbian social circuit. For over a decade, many of Australia’s drag king royalty mounted the stage at such events, including Melbourne-based Rocco D’Amore, burlesque performer Lillian Starr as drag king John Dark, queer performance duo Fancy Piece, and debonair gender illusionist Jayvante Swing.

Local drag king scenes developed in other capital cities within Australia owing to the passion and commitment of a large and rotating cast of amateur and professional performers, producers and promoters. But the drag king has faded from the thriving scenes he supported in Australia in the first decade of the 2000s. It’s difficult to pinpoint a single explanation or common source behind the scene’s demise, though it is clear that a number of factors are at work.

Gentrification, and the economic instability of commercial ventures for women, has seen a number of formerly iconic lesbian clubs and bars close worldwide or be co-opted into mainstream party scenes.

There are also important questions about language and identity. For example, the word ‘queer’ is increasingly replacing the word ‘lesbian’, as it is seen as more inclusive to other forms of female desire. Drag also sits uneasily with the emerging presence of trans and gender-diverse people, which may conflict with the performance of gender for comedy.

It may also simply be that those who attended drag king performances a decade ago are now of an age where going out mid-week to late night events has lost its appeal.

New kings

Combining drag queens and kings, Leigh has been a vocal advocate for evolving drag performance art. Even Darwin has seen an emerging bio-queen scene – where people who identify as female and “biological women” perform as drag queens – in its established drag culture.But there’s recently been a resurgence in drag king culture.

New events have started in Sydney and Melbourne. Sydney Heaps Gay organiser Kat Dopper feels there was a demand from younger queer women for a specific platform to try out drag. In Melbourne, well-known drag performer Lexi Leigh bills Lady Drag as “drag disco” that celebrates a diversifying drag community.

Drag culture more generally seems to be becoming more experimental and inclusive. It’s not just drag kings who must change with the times. Drag queen culture is experimenting with new forms that don’t rely on rigid gender identification and expression. Even drag’s more mainstream counterparts are responding to this call: RuPaul’s Drag Race’s ninth season marked the first time an openly trans woman performed as a drag queen contestant.

The success of these new events in Australia perhaps heralds a more permanent king fixture on the party scene. In becoming more inclusive, Australia may soon see a return of the king.

Strapped, packed and taking the stage: Australia’s new drag kings

Kerryn Drysdale, Research associate, UNSW

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Image: Some drag kings draw on facial hair to perform masculinity – photo by Sneakers