A significant amount of anticipation has met the film adaptation of Holding the Man (2015). Based on Timothy Conigrave’s 1994 memoirs of the same name, Timothy and John’s love story has a firm place in the gay canon. After penning a successful theatrical adaptation, playwright Tommy Murphy returns to the Tim and John’s story for the big screen.

A significant amount of anticipation has met the film adaptation of Holding the Man (2015). Based on Timothy Conigrave’s 1994 memoirs of the same name, Timothy and John’s love story has a firm place in the gay canon. After penning a successful theatrical adaptation, playwright Tommy Murphy returns to the Tim and John’s story for the big screen.

The film – directed by Neil Armfield – had its world premiere at the closing night gala for the Sydney Film Festival in June and was the centrepiece gala at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF) last weekend. The importance this film has to Melbourne was highlighted by MIFF’s artistic director Michelle Carey in a recent interview with the Star Observer:

It’s not just a screening – this is such an important story to put up there and screen as a piece of Australian cinema, as well as all the local resonances and the Melbourne story.

For those yet to read it, the book is turbulent and gut-wrenching. I remember reading it when I was in my first year at university following a recommendation from a new friend I had recently met in the queer lounge on campus. Like many others, reading the book was a rite-of-passage as I began to articulate my own gay identity. Holding the Man has been a pivotal text in the formation of an Australian gay identity.

Holding the Man intimately follows Tim’s 15-year relationship with John Caleo, the star of the school football team. Their story begins at Melbourne’s Xavier College, where their high school romance is filled with sneaky pashes, love letters and secret rendezvouses at night. This theme of forbidden love is made even more obvious through Tim’ role in the school production of Romeo & Juliet.

Tim and John’s years at Xavier College are lovingly captured in the film with their youthful infatuation adapted from key passages in the text, from Tim writing on John’s pencil case in class to the dinner party where they share their first kiss.

Early into the film, Armfield cuts to a later stage in their relationship, a transition that is particularly disorienting for the viewer. We learn that they have been together for 15 years and are both HIV positive. This devastating announcement is a harbinger for what’s to come for their relationship.

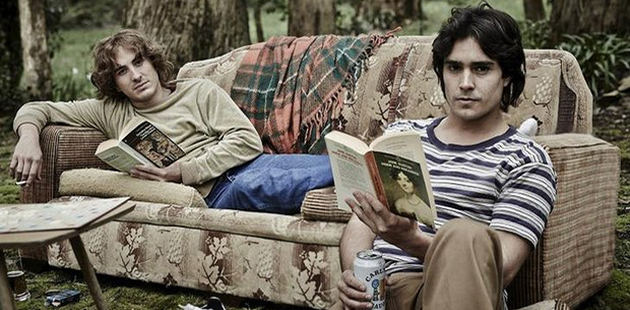

Casting actors to play characters in their teens through to their 30s is always going to be a difficult task. The film does manage to transition Ryan Corr’s Tim and Craig Stott’s John smoothly through the 15 years of the story. Their chemistry is palpable, which is imperative in order to convey the deep bond these two men had.

It’s important to note how funny the film is. Quite a few lines sparked laughter in the Sydney crowd, when I saw the film there. As John and Tim argue at a movie date, John complains that all he really wanted to do was see the film Nine to Five (1980) as he’d heard it was very funny. My personal favourite is Tim’s friend’s retort to a violent, homophobic pub patron: “I’m a dyke, ya dipshit!”

There is a charming, Australian irreverence to these characters, which balances out the impending heartbreak. This film isn’t ground-breaking when compared to other queer films that deal with a similar subject matter, such as Zero Patience (1993), The Living End (1992), The Normal Heart (2014), Parting Glances (1986) or The Witnesses (2007). Stories of middle-class white gay men have been told in abundance in comparison to other queer identities.

The film does, however, contribute to the small but growing list of Australian queer cinema to receive a limited theatrical release – Love and Other Catastrophes (1996), The Sum of Us (1994), Head On (1998), 52 Tuesdays (2013), The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), to name a few. More importantly, it captures a personal, Australian perspective of the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s.

Adapting a much-loved text is always a delicate task as the audience – familiar with the source material – can be fiercely protective.

This is a story that is held incredibly dear to those that read the book. As shattering as reading this book was, Conigrave’s book was a beautiful text that was informative during my early years at university. Many friends have similarly recounted to me how important this book was for them as they grew up.

The film adheres to the original text closely with key passages recreated in the film: Pepe’s dinner party, various sexual encounters and Tim calling John and asking, “Will you go round with me?”.

It also places a significant emphasis on the high school period with the final, devastating turn of events not being as drawn out as they were in the book. The book provides a distressing amount of detail at how totally destructive the disease was to the body during the crisis. The level of detail provided in the book was at times overwhelming – I could only ever read it in short bursts.

There is an affective power when one revisits a text such as Holding the Man. Sitting in the screening during the closing scenes – with an audibly sobbing audience – the sheer emotional toil the book had on me returned, particularly when the photographs of the real Tim and John appear before the closing credits.

It’s important that this emotional weight of this tragic period is told to younger Australians, and particularly gay Australians. If ever the devastating effect of AIDS in Australia was going to be told to a mainstream audience, Holding the Man has the potential to be that film.

Holding the Man, and bringing HIV/AIDS in Australia to a mainstream audience

Stuart Richards is Researcher and Tutor in Screen and Cultural Studies at University of Melbourne.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Image: Ryan Corr as Tim Conigrave and Craig Stott as John Caleo in Holding the Man